linkHow Coding Blog JAMStack Works

Basics of providing content over the internet are fairly straight-forward: Browsers will send requests to your server, and your server responds with some HTML potentially linked to some JS and CSS.

How and when you generate those HTML, CSS and JS content is however an entirely different thing. You might want to prepare them all in advance and have your server just serve them (pre-rendering), you might have your server generate them on the fly (SSR), or you might have your server ship some code to the browser that will then generate them (client-side rendering, SPAs). You might even generate requested content on the server and ship it with the code that would generate subsequently requested content on the browser (isomorphic).

There is one particular approach pretty suitable for blogs: you prepare most of the content before hand, then

serve it alongside code that would wire-in interactive bits and generate fully dynamic components. This is called

the JAMStack, and it is the approach used by coding.blog and

CODEDOC for content generation. In this post, we go through the reasons we chose this

approach, and how we implemented it.

linkWhy JAMStack?

To better understand why we chose JAMStack for coding.blog and how we set our further design goals, its good

to first have a general overview of methods of web content generation/delivery:

Pre-Rendering

Pre-rendering simply means preparing your content before-hand, i.e. in the build stage. This is the fastest delivery method, and allows you to simply use a CDN instead of writing a server for serving your content.

Server Side Rendering (SSR)

Instead of preparing the content, you can generate them on-the fly on your server, in response to each request. This is perhaps useful when your content needs to change based on incoming requests, and perhaps you need to get some data from some API to be able to create the content. However, this approach is obviously much slower than pre-rendering.

Client-Side Rendering and SPAs

Highly interactive and dynamic content means you need to generate content on the client-side. To avoid having content-generation code in multiple places (which is hard to maintain / scale), you could instead conduct all content generation on the client browser, having your server just ship the content generation code.

To avoid shipping the content generation code for each page of your site, you can also take control of the navigation on the client side, which leads to a Single Page Application (SPA for short). This is the basis of all modern front-end frameworks.

Client-side rendering means the user should wait extra time for being able to see the content, since typically servers are faster at generating content. It also messes up with SEO, since crawlers might not be able to even get the content in its full form (since they are not browsers) and so might not be able to properly index it.

Isomorphic Apps

To overcome these issues without spreading the content generation code in multiple places, the concept of isomorphic apps was introduced. The idea is to basically run the same code both on the server and on the client, while also shipping the code itself to the client alongside content rendered on the server.

The complexity of isomorphic apps inevitably brings extra constraints and overheads. For example, you need to re-hydrate the content on client-side, which means you are limited on how you manipulate that content (e.g. for React SSR, React needs to maintain full control of the DOM tree). These complexities also make it harder to optimize performance since many more components and their interactions are affecting it.

JAMStack Apps

Another approach would be to pre-render all your static content and then ship the code for filling in dynamic/interactive parts to the client. This would allow for the same delivery speed of pre-rendering without sacrificing interactivity of the content. It also implies a clear separation in the code-base as opposed to isomorphic apps: there is code that pre-renders stuff, and there is code that goes to client and makes stuff interactive.

The JAMStack architecture is specifically suitable for mostly static content, which makes it a perfect choice

for likes of CODEDOC (which is for documentation / guides about codes) and coding.blog (which is for blogs about

coding / programming). The simplicity of the workflow allows for easy optimization and high degrees of interoperability

and extensibility.

linkDesign Goals

While the JAMStack architecture was the most suitable for CODEDOC and coding.blog,

it mandates a split of content generation code into bits that are executed at build stage and bits that are

shipped to the client. This can quickly add a lot of complexity/overhead for any growing project, so we had to

find a solution that addressed this particular issue.

In other words, we needed to:

- have a shared component system

- easily mark client-side components so that they are not pre-rendered

- seamlessly where these components were to be rendered in the DOM tree

- conveniently and efficiently collect and bundle the code of these clients

- conveniently attach these bundles to pre-rendered content

Additionally, we wanted a minimal toolchain and stack with maximum extensibility and interoperability. Generally we wanted knowledge of HTML/JS/CSS to suffice for serious customization, which made a JSX-based syntax an optimal choice for our component system (specifically as Typescript supports it out of the box).

However, we couldn't use a library like React (or any VirtualDOM based solution) since its sensitivity to external changes to the DOM tree meant limitations on how the DOM is manipulated by extensions, either during pre-rendering or on the client. Besides, we needed our content to be as light-weight as possible, which simply prohibited relatively heavy-weight operations such as VirtualDOM diffing.

linkBasic Rendering

To satisfy our design goals, we created a JSX-based rendering tool which directly sits on top of DOM APIs. This is called CONNECTIVE HTML, and on a basic level is merely a wrapper of DOM APIs that allows using them via JSX:

1linkimport { Renderer } from '@connectv/html';

2link

3linkconst renderer = new Renderer();

4linkrenderer.render(<div>Hellow World!</div>).on(document.body);

For more dynamic/reactive content, we simply added plugins to allow rendering RxJS Observables:

1linkimport { Renderer } from '@connectv/html';

2linkimport { timer } from 'rxjs';

3link

4linkconst renderer = new Renderer();

5linkrenderer.render(<div>You have been here for {timer(0, 1000)} second(s).</div>)

6link .on(document.body);

This of course meant that for interactive components familiarity with RxJS was required, however, you generally do require familiarity with some reactive state management library to be able to properly create interactive components. RxJS might not be the easiest such library for people to dive in, but considering its widespread usage and the overall performance gain, we felt this was a compromise well worth it.

Fun fact: Historically CONNECTIVE HTML was developed first and CODEDOC as a tool to document it. However as a result of popularity of CODEDOC and subsequently

coding.blog, I haven't found the time to use it for its original purpose yet.

linkSDH Rendering

To meet the remainder of our design goals, we created a tool named CONNECTIVE SDH. SDH stands for Static/Dynamic HTML, which means this library allowed us to seamlessly create both static (pre-rendered) and dynamic (rendered on client-side) HTML content.

This is how CONNECTIVE SDH works:

linkStatic Content

For pre-rendering (or even SSR), the fact that CONNECTIVE HTML is pretty thin meant that we could simply combine it with JSDOM and add some nice functions for storing the results:

1linkimport { compile } from '@connectv/sdh';

2link

3linkcompile(renderer =>

4link <html>

5link <head>

6link <title>Hellow World Example</title>

7link </head>

8link <body>

9link <h1>Hellow World!</h1>

10link </body>

11link </html>

12link).save('dist/index.html');

Or for a more component oriented example:

1linkimport { compile } from '@connectv/sdh';

2linkimport { Card } from './card'; // @see [Component Code](tab:comp)

3link

4linkcompile(renderer =>

5link <fragment>

6link <h1>List of stuff</h1>

7link <Card title='🥕Carrots' text='they are pretty good for you.'/>

8link </fragment>

9link).save('dist/index.html');

1linkconst style = `

2link display: inline-block;

3link vertical-align: top;

4link padding: 8px;

5link border-radius: 8px;

6link margin: 8px;

7link box-shadow: 0 2px 6px rgba(0, 0, 0, .2);

8link`;

9link

10linkexport function Card({ title, text }, renderer) {

11link return <div style={style}>

12link <h2>{title}</h2>

13link <p>{text}</p>

14link </div>

15link}

linkDynamic Content

For dynamic components, i.e. components that are to be rendered on the client side, we needed to:

- Collect and bundle their code

- Attach that bundle to pre-rendered content

- Create placeholders to maintain their position in the DOM tree

With CONNECTIVE SDH, this process looks like this:

1linkimport { compile, save, Bundle } from '@connectv/sdh';

2linkimport { $Counter } from './counter'; // @see [Component Code](tab:comp)

3link

4linkconst bundle = new Bundle('./bundle.js', 'dist/bundle.js');

5link

6linkcompile(renderer =>

7link <fragment>

8link <p>

9link So this content will be prerendered, but the following component will be

10link rendered on the client side.

11link </p>

12link <$Counter/>

13link </fragment>

14link)

15link .post(bundle.collect()) // --> collect all necessary dependencies in the bundle

16link.save('dist/index.html')

17link .then(() => save(bundle)) // --> build the bundle and store it on fs

1linkimport { state } from "@connectv/core";

2link import { transport } from "@connectv/sdh/transport";

3link

4linkconst style = `

5link border-radius: 3px;

6link background: #424242;

7link cursor: pointer;

8link padding: 8px;

9link color: white;

10link display: inline-block;

11link box-shadow: 0 2px 6px rgba(0, 0, 0, .12);

12link`;

13link

14linkexport function Counter(_, renderer) {

15link const count = state(0);

16link return (

17link <div style={style} onclick={() => count.value++}>

18link You have clicked {count} times!

19link </div>

20link );

21link}

22link

23link export const $Counter = transport(Counter); // --> transports `Counter` to client-side

linkPlaceholders

In this example, Counter is a component that needs to be rendered on the client-side, i.e. it needs

to be transported to the client. This is done via this line of the code:

1linkexport const $Counter = transport(Counter); // --> transports `Counter` to client-side

The transport() function simply figures out the import path for Counter, and then creates a placeholder

component, i.e. $Counter, that also is marked with that information. If executed on the client-side,

it will return Counter itself, since there is no need to transport anything.

As a result, we now can use $Counter inside any context. If it is used during pre-rendering, then

it will be a placeholder that will be replaced with Counter on client-side, and if it is used on the client-side,

then it is identical to Counter:

1linkcompile(renderer =>

2link <fragment>

3link <p>

4link So this content will be prerendered, but the following component will be

5link rendered on the client side.

6link </p>

7link <$Counter/>

8link </fragment>

9link)

linkBundling

The Bundle class provided by SDH allows us to easily manage client-side bundles. We wanted to comply with a no-magic

approach for SDH, so we didn't want to hide bundle management inside some obscure serialization process:

1linkconst bundle = new Bundle('./bundle.js', 'dist/bundle.js');

As mentioned earlier, we need to collect all client-side components and bundle their code. The bundle object

provides the .collect() method specifically for that purpose:

1link.post(bundle.collect())

This will cause the bundle to scan the generated DOM tree and search for all transport placeholders (e.g. $Counter).

Since these placeholders are marked with the import path of their original component, the bundle object

can then collect all necessary import paths for creating a client-side bundle.

After collecting all client-side dependencies, we simply generate the bundle code:

1link.then(() => save(bundle));

SDH will first create an entry point for the client-side bundle, in which it imports all necessary components. It also adds some necessary code that would allow transport placeholders to replace themselves with their actual components when they reach the client.

Afterwards, SDH uses Webpack to create a bundle out of that entry file (the bundler and its configuration naturally can be overriden as well). Webpack's Tree-shaking, coupled with the fact that only components used within a scanned DOM-tree,

linkTransport Mechanism

Lets take another look at the line responsible for creating the transport placeholder of Counter:

1linkexport const $Counter = transport(Counter); // --> transports `Counter` to client-side

As discussed earlier, the transport placeholder, $Counter, needs to know its original component, i.e.

Counter, in order to replace itself on the client-side. This also means that it must know the exact import

path of Counter, so that it is able to communicate it to the bundle so that it can import it.

Since part of our goal with SDH was to avoid unnecessary complexities, we didn't want to make this

process super-complicated either. As a result, we added a simple rule: the transport() function MUST be called

in the file from which the original component is exported. This would allow the transport() function to take a look

at its own callstack and at the name of the component passed to it, and construct its import path.

linkPros

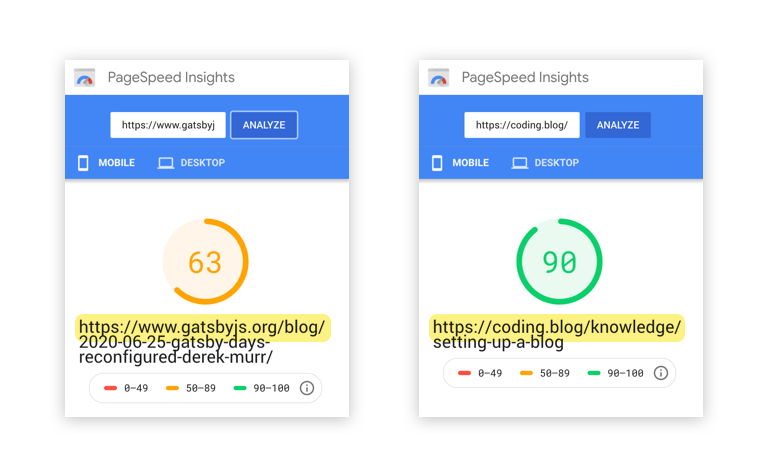

First and fore-most, this approach results in great performance. Most of the content is pre-rendered, and can be cached and efficiently delivered via CDNs, which means the browser gets its first response pretty quickly and is immediately able to display content afterwards. Browsers of course do tend to wait for some additional resources like scripts and stylesheets, however the scripts can also be deferred since they are not necessary for using the initial content (and the styles are typically pretty slim).

Obviosuly there is still room for improvement performance-wise, as for example right now fonts ARE throttling the pages unnecessarily. I am still not sure about inlining the styles vs loading them independently, since the former would yield faster page loads but the latter means more content is cacheable.

Besides performance, the SDH rendering approach also makes it exceedingly convenient for maintaining pre-rendered and client-side components alongside each other. You could easily turn any pre-rendered component into a client-side one (and vice-versa), and the bundles would automatically adapt to those changes. To avoid mistakenly pre-rendering client-side components, SDH also throws errors when it detects components trying to bind to browser events during pre-rendering.

More importantly though, the thin-ness and simplicity of all tools used provides extreme interoperability,

both with DOM APIs and with external tools. CODEDOC and its plugins frequently use APIs like document.querySelector()

both during pre-rendering and on the client side to find and manually replace/modify DOM elements. Because there

is no Virtual DOM that needs to remain in sync with the actual DOM, there is no limit in how you can manipulate

generated content.

linkCaveats

The SDH rendering approach is not without its own caveats as well. Here are the most important caveats we faced

while using SDH for CODEDOC and coding.blog:

linkTransport Safety

SDH makes it seamless to share code between pre-rendered components and client-side components. However, thats not always a good thing to do, as a lot of packages and codes are not designed to be used on the client-side.

In really terrible cases, Webpack will fail to even create the bundle. A worse case situation is when it does create the bundle, but is unable to tree-shake it properly, including huge chunks of unused code within the bundle.

linkSmooth Loading

Though CODEDOC (and coding.blog) pages are pretty light-weight with small and extremely cacheable shared resources,

still SPA-style loading offers a much better user experience.

To that end, we have even developed a specific smooth loading mechanism for CODEDOC and coding.blog that just fetches the requested

HTML and replaces designated parts of the DOM. This strategy works pretty well, so well in-fact that I suspect it is possible to

simply extract it into a separate package that can offer SPA-style navigation for any JAMStack app.

However, our smooth loading strategy hinges on the fact that major resources (such as fonts, scripts and styles) are shared amongst

various content pages. SDH does support bundle splitting, as any Bundle instance tracks whether another Bundle instance has already

taken care of a particular client-side component or not. However utilizing this feature naively still leaves some shared code (mainly

that of RxJS and CONNECTIVE HTML) duplicated across multiple bundles. It is possible to split those dependencies into separate bundles

as well, but right now that requires manual configuration of Webpack (or any bundler that is used) and it has yet to be tested in practice.

P.S. If you do not know what

coding.blogis, its an open-source blog platform that is designed to be a place for quality programming articles instead of ads, paywalls, etc. That is not just a mantra: we want to design a platform that systematically maintains high content quality through transparently priced curation services and open-ness of the platform itself.If you are interested, you can read more about it here. If you are someone who writes programming blogs and are looking for a fresh, convenient, extremely customizable open-source blog on a cool domain like

https://your.coding.blog, then checkout this piece and enlist in our prospective creators list if you choose to join us.

Why we chose JAMStack for coding.blog, instead of doing SSR, making an Singe-Page Application, setting up an isomorphic Javascript project, etc. Also details on how we implemented it using SDH rendering, and how it gave us incredible performance, flexibility and developer experience.

Javascript, Frontend, React, JSX, Typescript, GatsbyJS, JAMStack, Isomorphic, SSR,

article

summary_large_image

How Coding Blog JAMStack Works

How Coding Blog JAMStack Works

@lorean_victor

@coding_blog

Why we chose JAMStack for coding.blog, instead of doing SSR, making an Singe-Page Application, setting up an isomorphic Javascript project, etc. Also details on how we implemented it using SDH rendering, and how it gave us incredible performance, flexibility and developer experience.

Why we chose JAMStack for coding.blog, instead of doing SSR, making an Singe-Page Application, setting up an isomorphic Javascript project, etc. Also details on how we implemented it using SDH rendering, and how it gave us incredible performance, flexibility and developer experience.